Choose Excellence Over Perfectionism

“The important work of moving the world forward does not wait to be done by perfect men”

– George Elliott

We all know the feeling…

We start a diet, and we stick to it perfectly.

Then suddenly temptation gets the better of us…

…we eat one bad thing and boom.

We binge like there’s no tomorrow and feel guilty.

This is all or nothing thinking, a classic symptom of perfectionism.

But perfectionism doesn’t just affect our diets, it affects our confidence, our relationships, and our work…

…and it needs to be stamped out.

In this article, you'll learn the theory behind why perfectionism is so destructive, and the exact strategies used by master creators to navigate this complex psychological malady.

Why Learning From Failure Is Essential

In my guide to overcoming procrastination, I briefly explained that we often know what we should do in order to succeed, but often find the idea of following our own advice too frightening to act upon.

If we fail under someone else’s council then surely it is not our competence that is questionable, but the council we have received.

We seek out external resources (like this article) to lift some of the creative responsibility from ourselves and provide a way of rationalizing any potential failure.

The fear of creating art and the fear of following our own advice, I believe, are symptoms of our proclivity to take failure personally.

We live in a society where everyone basically gets given the same opportunities to succeed, and so our eventual position in life, including the successes and failures along the way, are thought of as deserved.

Society’s seeming equality, coupled the media’s humiliating depictions of failure and the unrealistic models of perfection they present as successes, causes us to avoid failure so much, that we often also avoid taking the risks that are necessary to succeed.

But if you read the biography of any successful person, you will quickly discover that failure and risk are not mere obstacles in the way of success, but rather they are the vital stepping stones along the ascent.

It has been well documented by psychologists that there is a large correlation between how often a person fails and how likely they are to succeed.

The most successful sportspeople, scientists, and artists have all failed more than their less-successful contemporaries.

It could be no other way. Learning requires practice and experimentation. Success requires depends on the ability to consistently overcome failure and bounce back with newfound wisdom.

The lesson?

“Failure is an inescapable part of life and a critically important part of any successful life. We learn to walk by falling, to talk by babbling, to shoot a basket by missing, and to color the inside of a square by scribbling outside the box. Those who intensely fear failing end up falling short of their potential. We either learn to fail or we fail to learn.”

— Tal Ben-Shahar, The Pursuit of Perfect

Even Plato Had Self Doubt

We tend to think of highly successful celebrities as almost mythical super-humans composed of a separate genetic material than ourselves.

You could argue that the media heightens their extraordinariness to make them more captivating and glamorous. I believe that’s an element of it, but not the whole picture: I think we actually want celebrities to have an other-worldly quality to them, not just to make them more captivating, but so that we don’t suffer the envy that would otherwise occur if we thought their accomplishments were within reach.

It is no coincidence that we envy our slightly higher-paid co-workers while we happily sit and admire the billionaire entrepreneurs streamed into our homes every night.

It's not my place to tell you what you can or cannot do. But it is worth just recognizing that the main difference between you and those "perfect people" you aspire to be like is, ironically, their ability to embrace imperfection, endure suffering, persist against setbacks, stay poised in uncertainty, and override self-doubt.

The Greeks called it hubris. It has been called sinful pride, which is, of course, a permanent human problem. The person who says to himself ‘yes I will be a great philosopher and I will rewrite Plato and do it better’ must sooner or later be struck down by his grandiosity, his arrogance and especially in his weaker moments will say to himself ‘who? Me?’ And think of it as a crazy fantasy or even fear it as a delusion. He compares his knowledge of his inner private self with all its weakness, vacillation and shortcomings with the bright shining perfect and faultless image he has of Plato. Then of course he’ll feel presumptuous and grandiose. (What he doesn’t realise is that Plato, introspecting, must have felt just the same way about himself but went ahead anyway, overriding his doubts about himself.)

– Abraham Maslow

If you’re hoping to succeed without encountering failure, by implication, the only standard you are willing to accept from yourself is perfection. And if you haven’t realized yet, perfection is… not so perfect.

The Root of Perfectionism: All Or Nothing Thinking

“The maxim “Nothing but perfection” may be spelled “Paralysis”

– Winston Churchill

People with perfectionism often wear it like a badge of honor.

"I’m a perfectionist and I accept nothing but the best. If I feel anxious and unhappy, so be it. It is the only road to success. No pain no gain."

While we now know this attitude is counter-productive, the perniciousness of perfectionism goes far beyond procrastination, time-wasting, and the failure to learn from failure.

Perfectionism, left unchecked, can spread throughout our lives like a virus causing us to impose imperfections upon things that, by nature’s standard, are just the way they should be.

Here’re three examples of how perfectionism can distort our reality beyond the realms of productivity:

1) Perfectionism can lead to mental disorders.

Perfectionists think in an all or nothing attitude: If they are not supermodels, they are ugly; if they are not slim, they are fat; if they are not the smartest, they are the stupidest; if they are not first, they are last; if they mess up one part, the whole is messed up; if they want to get fit, they run a marathon.

This attitude is obviously a terribly unhealthy one. Thinking in this binary manner will inevitably lead to self-sabotage, or worst yet a mental disorder.

Psychologists have studied perfectionists and conclude that they are more at risk of developing eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia than the rest of us.

If they eat one wrong food, they feel as though their whole diet is ruined, binge like there is no tomorrow, feel guilty for binging, and binge some more to try and spread pleasure over the guilt.

2) Perfectionism causes bad relationships.

If our world view proselytizes anything less than perfect as abominable, we will assume others also share this belief and, as a result, become hypersensitive to any minor fault another may perceive in us.

Along with this hypersensitivity will come defensiveness: the antithesis of intimacy. For there can be no intimacy when there is defensiveness because true emotional intimacy stems from the trust we place in others by making ourselves vulnerable and imperfect in their company.

3) Perfectionists have low self-esteem.

Nathaniel Brandon, the world’s leading authority on self-esteem, explained in his book The Six Pillars Of Self-Esteem, that an essential component of self-esteem is the ability to be self-accepting. But how can a perfectionist ever be self-accepting if, to use the old cliché, "nobody is perfect?"

The problems with perfectionism are clear and disconcerting.

But without a viable solution, we are no better off than they are. Luckily, there is one.

The Parable of Stanley Kubrick’s Perfectionism

Stanley Kubrick, one of history’s greatest film directors, after finishing Full Metal Jacket in 1987, immediately began searching for his next novel to adapt.

In the typical Kubrick fashion, he began by voraciously reading everything in sight and even employed teams of researchers, to summarise, the books he didn’t have the time to read himself.

During this intense search, which he did prior to every film, the only sound his assistant, Leon Vitali, would hear from his office, for months on end, was, "The thud of books hitting the floor."

In 1990, hundreds of thuds later, Kubrick's three-year search came to an end when he found the book, Wartime Lies. Its subject matter was dark and serious. It was based on the atrocities of World War II, in particular, the Holocaust.

Now the next stage of Kubrick’s research began: to learn everything humanly possible about World War II and the Holocaust.

Kubrick’s method for researching a film was simple. When discussing the research he did for his film Dr. Stangelove, a satirical comedy about the cold war, he described his process as follows:

"I stop reading when I can read new books on the subject and fail to learn anything new."

If you are already familiar with Kubrick, examples of his obsessive attention to detail should not surprise you. If you aren’t here are five examples:

- He was famous for shooting an excessive amount of takes. When filming The Shining, he broke the world record by shooting the same scene 148 times.

- He would often measure his film’s ads in newspapers and call them up if they did not have the exact dimensions (to the mm) for which he had paid.

- He wore the same boots as the astronauts on the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey so that the footprints on the moon would all be identical to one another.

- Concerned that his cats were overdrinking, he called up his vet to find out how many milliliters there were in the average cat slurp. His vet didn’t know. Kubrick later phoned him back with the answer.

- Not being satisfied with the tightness of the lids on the boxes he used for storage, he designed his own and called up the local box manufacturers with the dimensions. His box is still in production.

If you haven’t realized yet, Kubrick was a massive perfectionist. And similar to the previous examples on the problems with perfectionism, Kubrick’s immersion into the depressing world of World War II, for Wartime Lies, had costs far and beyond the realm of work.

His wife Christiana, in Jon Ronson’s documentary Stanley Kubrick’s Boxes, recalled, “This was a very dark time period for Stanley… he became depressed’ and would often ‘sit in the corner and sob.”

Unbeknownst to Kubrick, another filmmaker was working on a project with similar themes to Wartime Lies. During the last two years of Kubrick’s pre-production, ending in 1993, Steven Spielberg, researched, directed, edited, and released a film called Schindler’s List. It went on to win seven Academy Awards including the coveted Best Film and Best Director.

Needless to say, Kubrick immediately shut down production on Wartime Lies and didn’t release another film for a further six years, making it twelve years of inactivity as a director.

Stanley Kubrick was obsessive in his pursuit of perfection. And while his films are undeniably masterful [1], he suffered the common perfectionism ailments: unhappiness and time-wasting.

Steven Spielberg, meanwhile, strove not for perfection but excellence.

He was happy to delegate roles, focus on the big picture, work within deadlines, leave the box making to the box makers, cat slurping to the cats, and world records to the perfectionists.

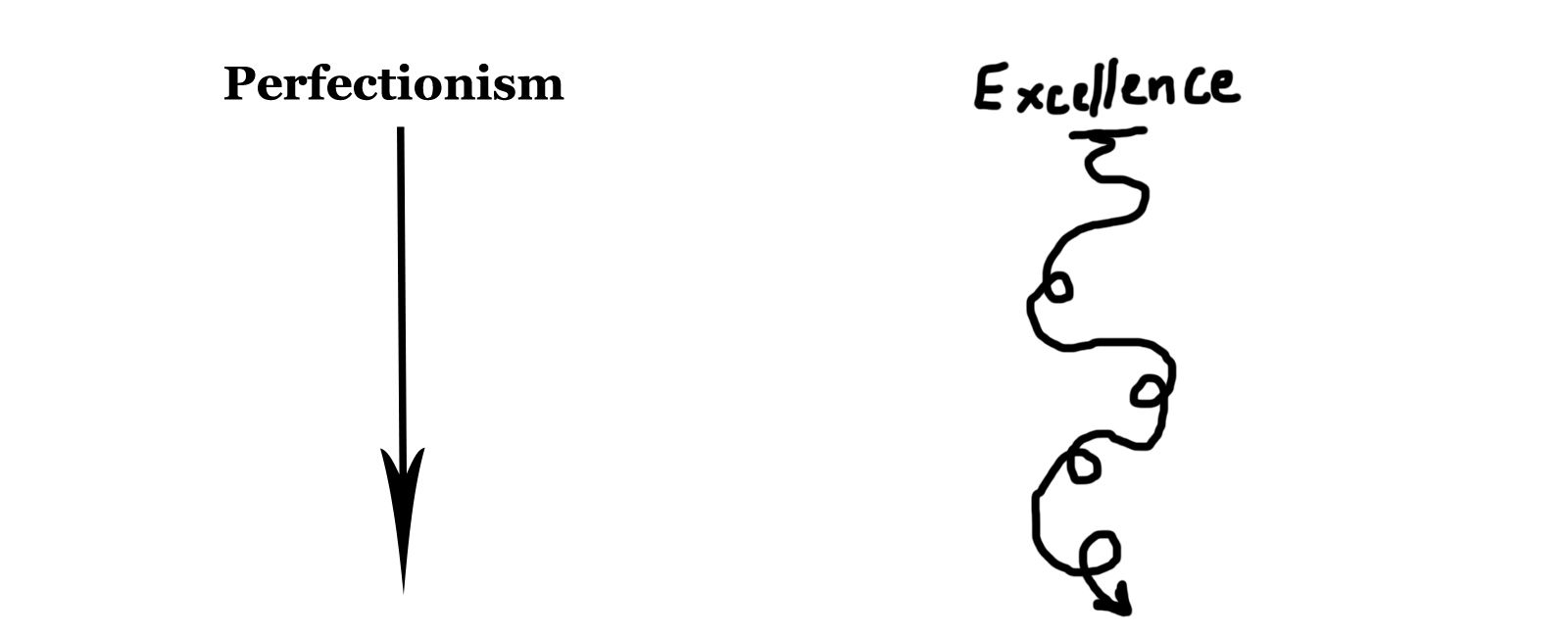

Aim for Excellence, Not Perfectionism

The perfect antidote to perfectionism is a change in mindset.

Instead of seeking things to be perfect, you aim to make them excellent.

Those who embody this principle:

- See failure as an opportunity to learn

- Understand the path to success is meandering

- Allocate time reasonably depending on the task

- Focus on the 20% that provide 80% of the results

- View progress as a slow and gradual

- Understand that nothing worth doing is easy

- Accept themselves as a constant work in progress

- Enjoy the process as much as the outcome

- Never neglect their wellbeing

Overcoming perfectionism is not straightforward and easy.

Perfectionists will try to interpret the difference between perfectionism and excellence as binary. It is not. It is a continuum. No one is perfectly perfect or perfectly excellent.

Perfectionists, in trying to overcome their perfectionism will often try to do so with the same rigid perfectionism that landed them in trouble, to begin with. You must resist this paradoxical temptation and allow yourself to be human, even if it means, at certain moments, embracing your perfectionism (more on this in my ebook).

To make the change out of perfectionism and switch paths to the pursuit of excellence, you have to keep reminding yourself about your new criterion as you work, always asking questions like:

- Is this excellent?

- I know it's not perfect, but is it excellent yet?

- What needs to be done for this to become excellent?

- Will there be diminishing returns if I try improving this much more?

By regularly asking yourself questions like this, you can, over time, begin to recalibrate your standard for success.

[1] Steven Spielberg described Stanley Kubrick as ‘the best filmmaker who will ever live.’ I’m not in disagreement with this. His work is astonishing. I’m simply highlighting the (sometimes unnecessary) sacrifices perfectionism demands. You don’t have to be the best that will ever live at something, to be successful at it.